In this new year, I hope to get back to a regular writing schedule. I made it through the third Christmas since Aaron died. I put out most of my decorations this year. Aaron loved Christmas and figured out how to get home to spend it with us most years. This year, my husband and I went on a road trip adventure to spend the holiday with our middle son and youngest grandchildren. They are pure joy.

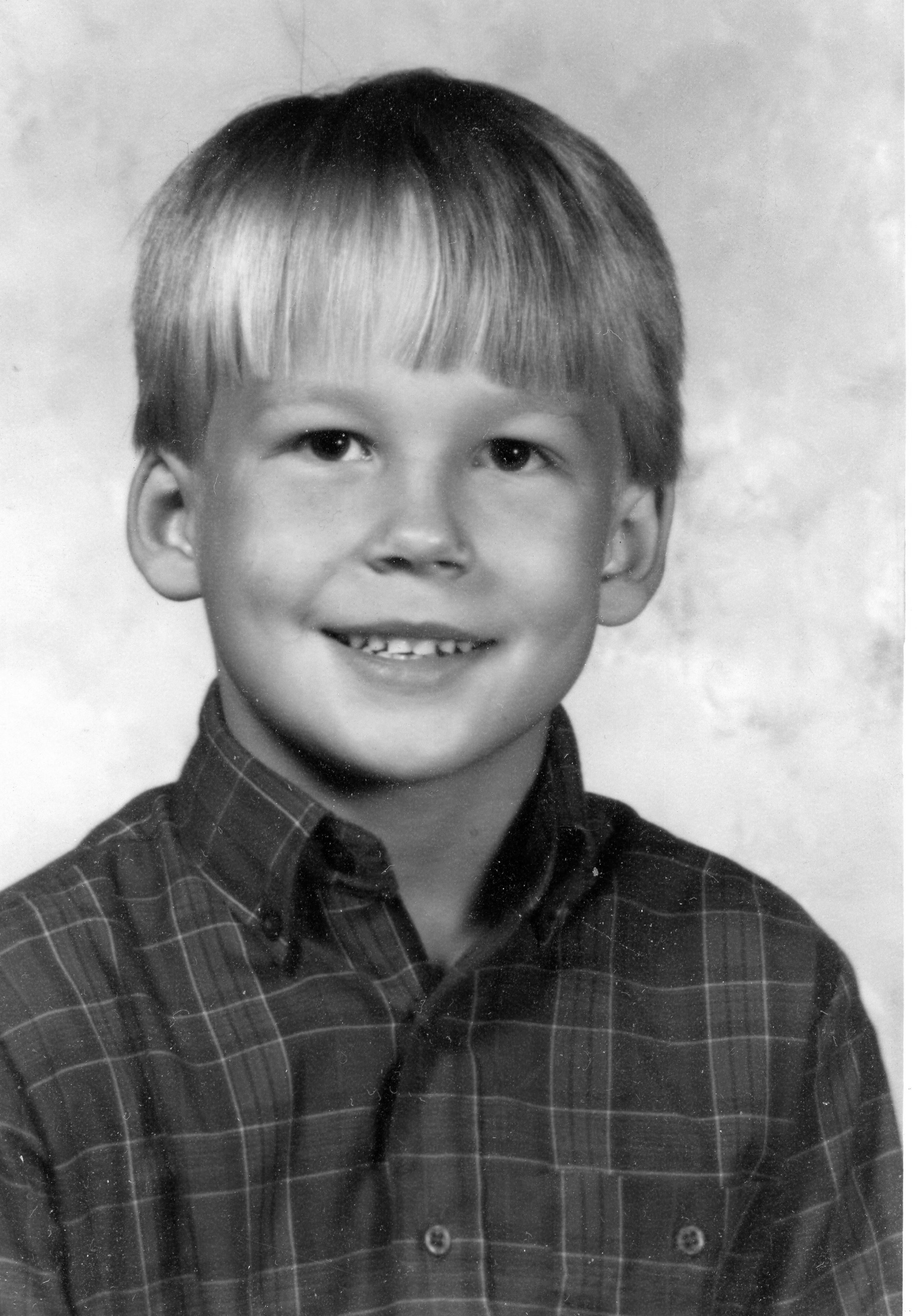

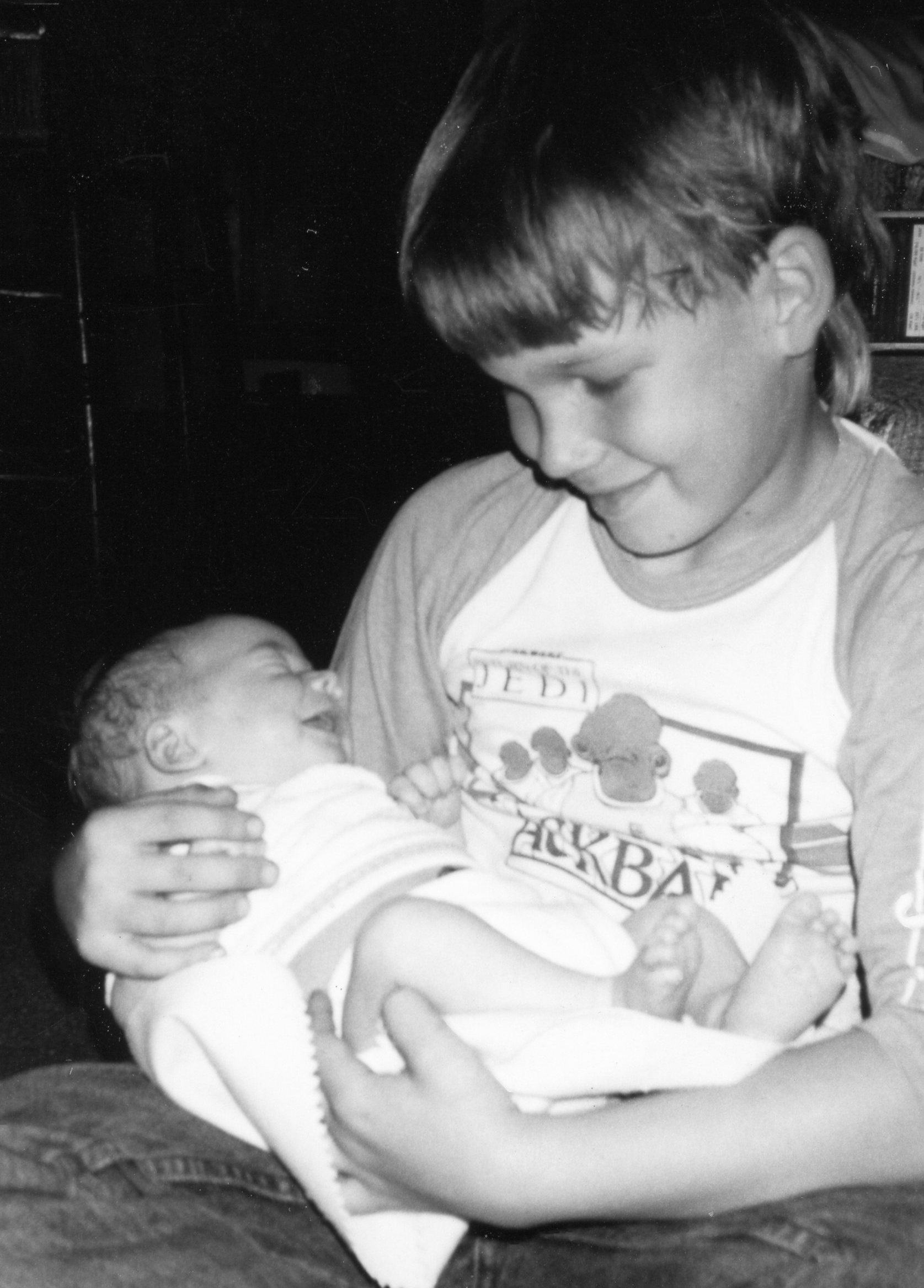

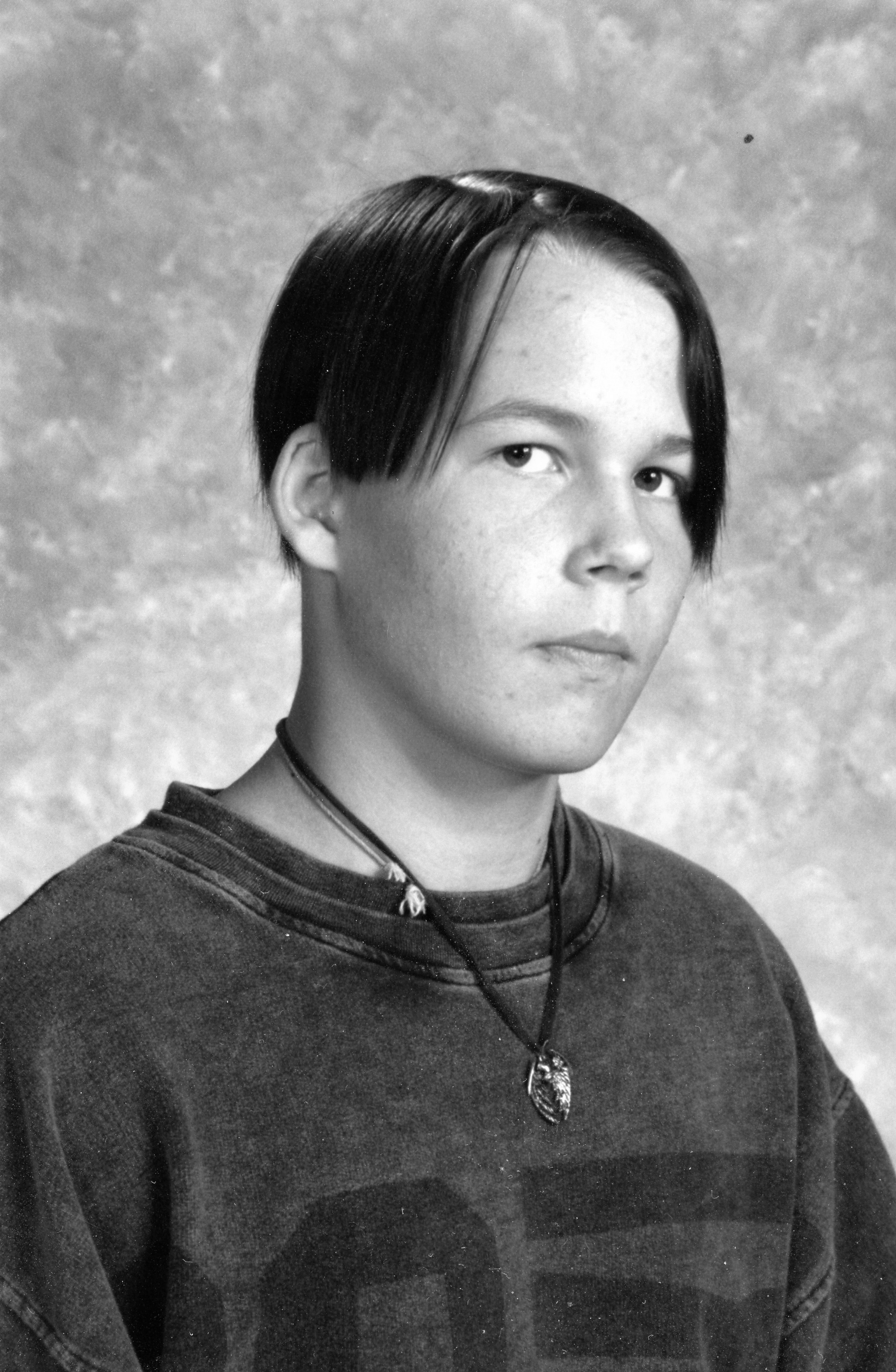

Aaron’s brothers benefitted from our having to become much more skilled parents. He taught us what was most important and what mattered least. We learned to focus on their strengths and balance time to assure that they experienced themselves as competent. Yet, Aaron’s brothers lived with his long shadows cast across even our joy. Each milestone celebrated with his younger brothers also reminded me of one that Aaron would never see; scout campouts, middle school, high school, team captain, prom, so many graduations, so many school career preparations … this Christmas also had those shadows.

A tragic consequence of Aaron having reached his lifetime maximum mental health benefits at twelve years old was that we lost the benefit of any vetting of services. That is how we got to Straight Inc. It seemed better than relinquishment to the state to access care which was the hospital recommendation. I so want to go back in time and tell them all to keep their opinions and just take him home instead, but I can’t go back. Aaron came out of Straight Inc at fourteen years old, traumatized and terrified. His dad and brother and I had also experienced trauma, having traded in the home we built in the community we knew for a dark, run down rental in a far away Dallas Texas, in a neighborhood that hated our family and especially the 183 youth that we took into our home at the rate of three to nine a night over the long nine months we operated a host home for Straight. The neighbors were loud and clear in their opposition to our living among them. We gave up the support of friends, family, and church, the security of work, and trusted our precious son to an unlicensed facility who not only lacked the most basic skills needed to help him build mental health, they abused him. Across the country, promising practices such as wraparound sought to identify and build youth strengths, and to wrap supports around youth like Aaron in their communities rather than send them far away to institutions. But no one in our community knew anything about Wraparound or any of the other emerging practices that might have changed our course.

After Straight no local counselors or other mental health professionals knew what to do. Their toolbox contained only the tired behavioral tools that we had already worn down. They did not want him in their groups because they feared his influence on the other participants. They did not know how to put the psychosis genie back in the box for him and it would be years before early intervention and prevention programs with best practices for psychosis would be developed. Because they did not know what to do with a fourteen year old trauma survivor who heard voices and ran from demons they could not see, the professionals we had access to used the only understanding they had. Their labels framed their understanding (or lack thereof) which cycled back to the behavioral models that had already failed, and whose damage was already overdone. The sanctioned mental health professionals did not know what to do with either early psychosis or trauma. There were long wait lists for the public system which at least had some experience with severe mental illness, if not much efficacy. In Texas, these problems persist today.

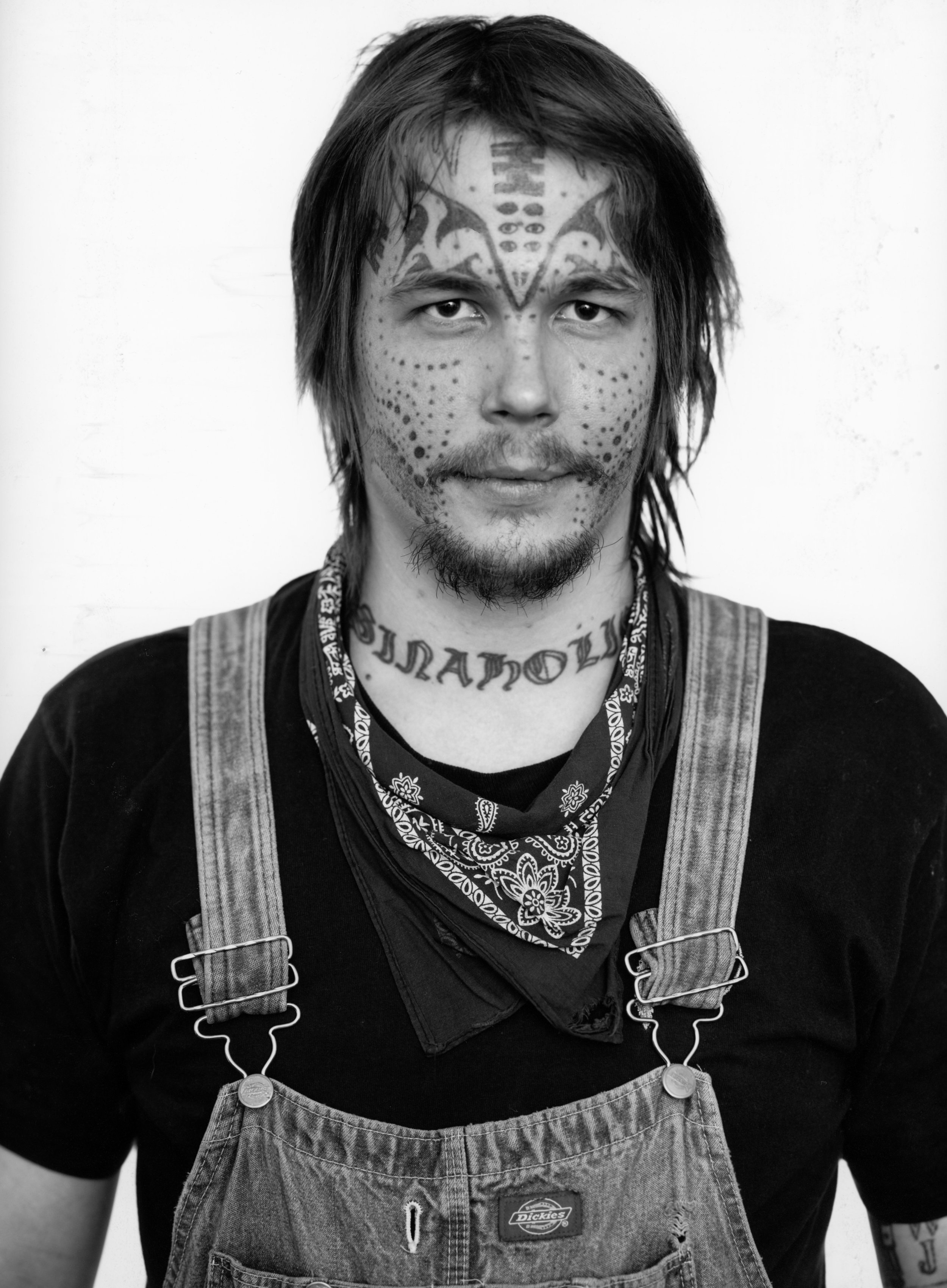

As I began to write this blog a few months ago, I was beginning to work on writing my experience as Aaron left home for the streets at age fifteen in the book. This may be why I allowed myself to get distracted and let such a long time lapse before getting back to the writing for this blog. That period after Straight was among the most painful periods in my life. Straight itself was horrible but I had been ignorant of the torture Aaron was experiencing there were plenty of people telling me a miracle was just around the corner. I had hope, however misguided, and now that was gone. I knew Aaron was in peril and I just could not keep him safe. Initially, he stayed close by in Deep Ellum, near downtown Dallas living in abandoned buildings. I created flyers and another former Straight host home mom and I walked the streets in the summer heat, posting them on dirty store windows and rough wooden utility poles, asking every passersby if they had seen him. We gleaned no information but later found out that he followed behind us collecting the flyers which he used to wallpaper his squat.

It was not long after that he began hopping trains to whatever city they stopped in. Before cell phones, we established an 800 number that he could call home with. On a bad day, when his paranoia and delusional thoughts ruled, he might call home four or five times a day. We would work through what threats were likely real and which were probably not. For a long time we tried to make him come home and stay, but there weren’t resources in Texas to help us support him.

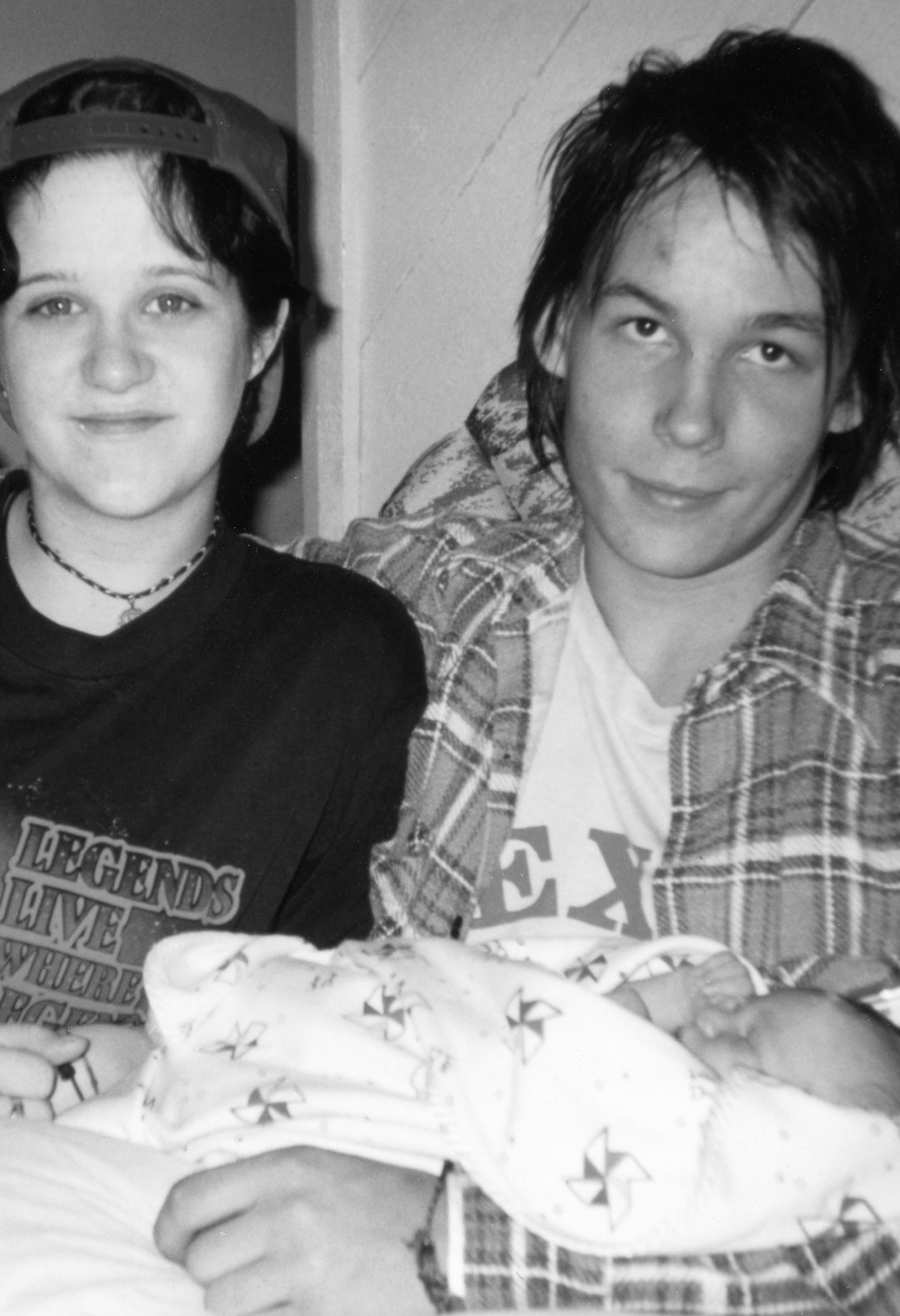

Regrettably, we resorted to the justice system in an effort to force Aaron to stay home. He just learned more street skills and was recruited by predators and hate groups. They were more than willing to create the illusion of belonging for him. Later, a staff member walked him out the door of the state’s juvenile justice “treatment” facility and told him to just leave. He was harassed and beaten by our local police force. The travelling homeless youth were at least a big step up from the terrifying skinhead gangs. Other traveling youth began to call my 800 number, sometimes in crisis, sometimes just to talk, and sometimes to let others across their network know where they were from San Francisco, New York, Cincinnati, New Orleans, Portland, Montreal, Toronto, to Vancouver. They traveled freight trains across the US and Canada.

I became an occupational therapist because I could not curl up in a ball and die. However odd our routines, I was still Aaron’s primary support and I had two younger children. I wanted to contribute to the lives of families like ours and children/youth like Aaron. I knew the solution could not rely only on remediating psychosis or depression or mania or anxiety or any of the behavioral labels we went through. It could not rely solely on resolving symptoms or behavioral issues. I was a skeptic but in occupational therapy I found a discipline I could use to help people figure out how to live a life anyway. Our focus is on helping people identify what they want and need to do and very pragmatically on what facilitates or inhibits participation.

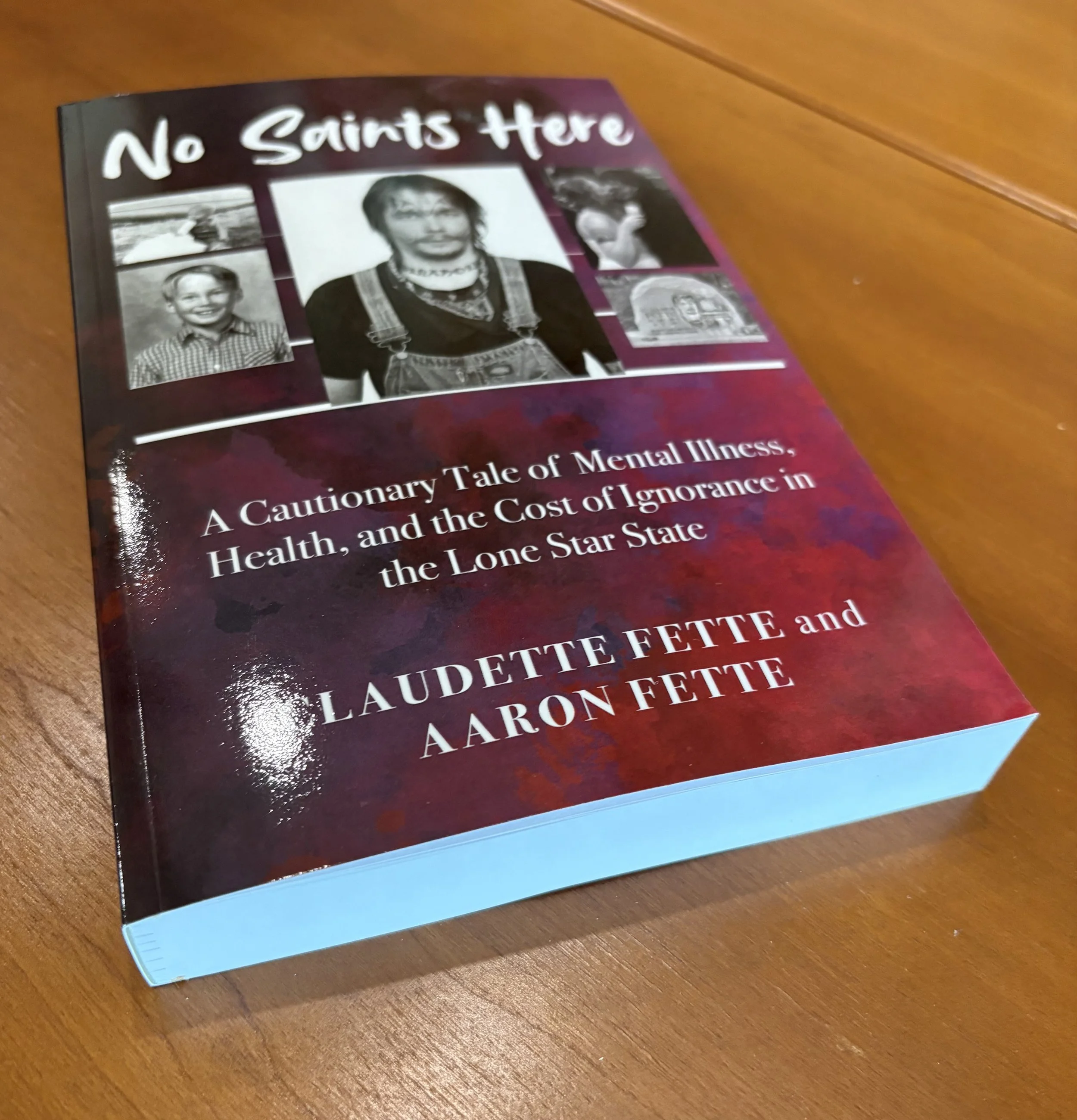

Aaron has contributed much to the field of mental health. His younger brother became a MedPsych physician (meaning he is a physician trained and certified in both internal medicine and psychiatry) and is practicing and teaching other physicians. I practice occupational therapy in mental health and teach to attempt to create the potential for more robust resources for people living with mental health needs. I hope Aaron’s book gets his voice and experience out and that we can use it to accelerate progress for children, youth, and families, perhaps before another twenty five years pass.

Occupational therapists use occupation or doing as our process in therapy. We are often problem solvers. We might modify environments to meet people where they are and/or help individuals build their adaptive capacity and skills so that the challenges they face become doable. We should be where it is that people need and want to do things, whether that is at home or elsewhere in the community. What we do looks very different person to person. It could be focused on getting dressed, preparing breakfast or accessing transportation for someone who needs modifications due to the impact of a physical injury or disease. It might mean teaching someone with sensory sensitivities strategies to manage difficulty tolerating sights, smells, or textures effectively so they can enjoy a picnic with friends and family. It could be building a game with a teenager with a trauma history to teach and practice effective coping strategies. It could be building a visual schedule with a mom who cannot read but needs to learn to care for her child with a disability. It could be setting up exercise routines and practicing cooking healthy meals for someone with diabetes brought on by their psychotropic medication. It might mean building and sustaining a recovery group/community for people with mental illness. We individually tailor active strategies that enable what people want and need to do. We have been working with people to build capacity to do what they want and need to do for more than 100 years, and we began this work with people with mental illness when traditional practice was to confine them to squalid institutions. Way back then we began by building healthy routines and habits, and productive occupations to enable people dignity and increased quality of life.

Unfortunately, Texas still does not recognize occupational therapists as mental health professionals, so generally people with mental illness are about the only disability population who has almost no access to us. Generally this is because the very disciplines who did not know what to do for Aaron are concerned that we will encroach on what they see as their turf and have opposed legislation that includes us. They cannot see what they do not know how to do. They still often lack the whole range of skills needed to support youth and families living with severe mental illness. Certainly they are unfamiliar with the range of disciplines and practices that people with mental illness benefit from in other places as well as multidisciplinary models that include occupational therapy from early psychosis prevention to community outreach models. I still practice in mental health all over my community and I teach to prepare new therapists to support people with mental illness in whatever other practice areas they may encounter them, and in an attempt to assure that someday there will be more robust supports for youth (and later adults) like Aaron who present with symptoms beyond the skill sets of our current systems.

I would like to say that, twenty five years after Aaron landed on the streets, families in my community have access to more responsive and skilled systems, but I know this is not true. We have made some progress, foremost that there is a kind of limited access to a version of wraparound in our community mental health center. It does provide a very prescriptive menu of supports that can be useful, but it falls far short of fidelity to the model’s principles which we will discuss in a later blog. And while we are not supposed to have wait lists, we do. They are just renamed and called “interest lists” and families in crisis still have long waits. Texas has passed, but not funded, laws that are supposed to build capacity for Multitiered Systems of Support in Texas schools which would make a giant leap forward should they come to pass. Trauma Sensitive/Informed School training seems to have some traction in many areas. These are all hopeful developments. And our Community Resource Coordination Groups have been sustaining since Aaron’s crisis, but like us, most families have no idea they exist.

Desperate families still come to the end of their resources and their children are still at risk. We have family partners inside the community mental health centers but most families do not have access to them and they are constrained by the system that provides their salary. Independent family to family resources are few and far between, and most of us are volunteers which limits the time we have. There is much to be done.